巴菲特致股东的信(1993年)

⑦普通股投资

普通股投资

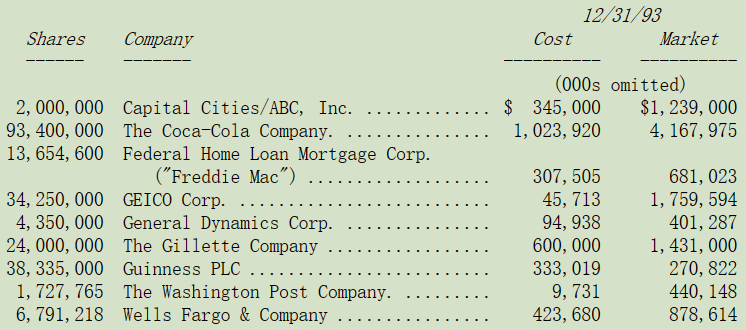

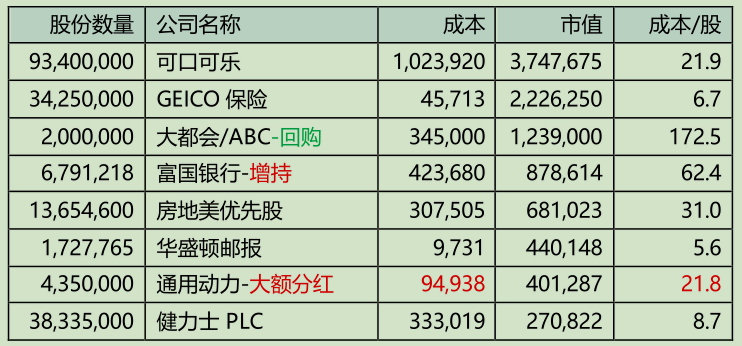

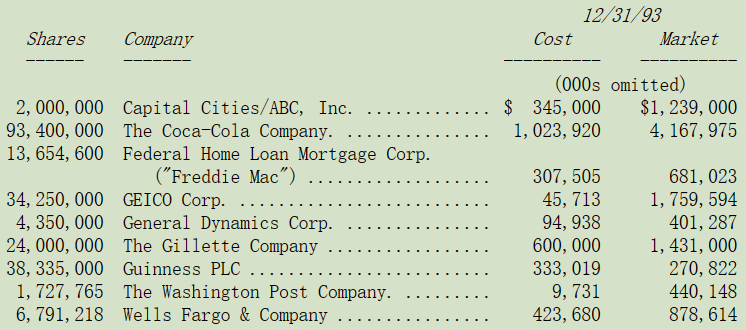

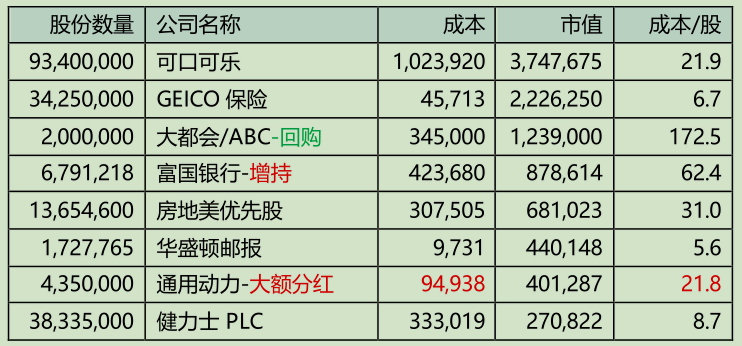

下表是我们超过 2.5 亿美元以上的普通股投资,一部分的投资系属于伯克希尔子公司所持有。

看到今年所列的投资与去年竟如此的相似,你可能会认为本公司的管理层实在是昏庸到无可救药的地步,不过我们还是坚持相信,离开原本就熟悉且表现优异稳定的公司实非明智之举,这类的公司实在是很难找到更好的替代。

有趣的是,企业经理人在聚焦本业时,从来不会搞错状况,母公司是不会单纯因为价格因素就将自己旗下最优秀的子公司给卖掉。公司 CEO 一定会问,为什么要把我皇冠上的珠宝给变卖掉?不过当场景转换到其个人的投资组合时,他却又会毫不犹豫地,甚至是情急地从这家公司换到另一家公司,靠的不过是股票经纪人肤浅的几句说辞,其中最烂的一句当属:你不会因为赚钱而破产。你能想象要是一家公司的 CEO 用类似的方式,建议董事会将最有潜力的子公司给卖掉时,后者会如何反应。就我个人的观点,适用于企业经营的原则也同样适用于股票投资,投资人持有一家优秀公司的部分股权,应当像拥有全部股权一样,表现出相同的坚韧。

先前我曾经提到若是在 1919 年以 40 美元投资可口可乐会获得怎样的财务结果。1938 年在可乐问世达 50 年且早已成为美国的代表产品之后,财富杂志对该公司做了一次详尽的专访。在文章的第二段作者写到:每年都会有许多重量级的投资人看好可口可乐,并对于其过去的辉煌记录表示敬意,但也都做下自己太晚发现的结论,认为该公司已达巅峰,前方的道路充满了竞争与挑战。

没错,1938 年和 1993 年一样,确实充满了竞争。不过值得注意的是,1938 年可口可乐一年总共卖出 2.07亿箱的饮料(将当时加仑数换算成现在 192 盎司的箱子 8*24 瓶),但是到了 1993 年该公司一年卖出饮料高达 107亿箱,对这家当时已经成为市场领导者的公司,在后来销售量又增长了 50 倍,对于 1938 年加入的投资者来说,Party 根本还没有结束,虽然在 1919 年投资 40 美元在可口可乐股票的投资人(含将所收到的股利再投资),到了1938 年可获得 3,277 美元,但是若是在 1938 年重新以 40 美元投资可口可乐股票,时至 1993 年底,还是照样可以成长到 25,000 美元。

我忍不住想要再次引用 1938 年财富杂志的报导:实在是很难在找到像可口可乐这样兼具规模而且又能持续数十年保持不变的产品。如今又过了 55 个年头,可口可乐的产品线虽然变得更广泛,但令人印象深刻的是,这种描述还依旧适用。

查理跟我很早就意识到,在一个人的投资生涯中,做出上百个明智的投资决策实在太难了。随着伯克希尔资金规模日益扩大,放眼整个投资世界,可以大幅影响本公司投资成效的机会已越来越少,因此,我们决定采取一种策略,只要求自己在少数的时候够聪明就好,而不是每回都要非常的聪明。所以我们现在,只要求每年出现一个好主意就可以了(查理提醒我今年该轮到我了)。

我们采取的策略,排除了我们遵循的标准多元化教条。因此,许多学者便会言之凿凿的说我们这种策略比起传统的投资策略,风险要高的许多。这点我们不敢苟同,我们相信集中持股的做法同样可以大幅降低风险,只要投资人在买进股份之前,能够提高自身对于业务的理解程度,以及对于竞争优势熟悉的程度。在这里我们将风险定义与一般字典里的一样,指损失或伤害的可能性。

然而,学术界却喜欢以不同的方式定义投资的风险,认为是股票或股票组合价格相对波动的程度,也就是个别投资相较于大量股票波动的幅度,运用数学与统计方法,这些学者能够计算出一只股票“精确”的β值,代表其过去的相对波动率,然后围绕这一计算,建立一套晦涩难解的投资与资本配置理论(数学上的胡言乱语),然而,在他们渴望用一个统计数据来衡量风险时,他们却忘了一项基本的原则:宁愿要模糊的正确,也不要精确的错误。

对于企业的所有权人来说,这是我们认为公司股东应该有的想法,学术界对于风险的定义实在是有点离谱,甚至于有点荒谬。举例来说,根据 Beta 理论,若是有一种股票的价格相对于大盘下跌的幅度更高,就像是我们在1973 年买进华盛顿邮报股份时一样,那么其风险远比原来高股价时还要更高,那么要是哪天有人愿意以极低的价格把整家公司卖给你时,你是否也会认为这样的风险太高,而予以拒绝呢?事实上,真正的投资人喜欢波动都还来不及,本杰明·格雷厄姆在《聪明的投资者》一书的第八章便有所解释,他引用了市场先生理论,市场先生每天都会出现在你面前,只要你愿意都可以从他那里买进或卖出你的股票,只要他越沮丧,投资人拥有的机会也就越多,这是因为只要市场波动的幅度越大,一些超低的价格就更有机会出现在一些好公司身上,很难想象这种低价的优惠,会被投资人视为对其有害。对于投资人来说,你完全可以无视于他的存在,好好地利用这种愚蠢的行为。

在评估风险时,Beta 理论学者根本就不屑于了解这家公司到底是在做什么,他的竞争对手在干嘛,或是他们到底借了多少钱来营运,他们甚至不愿意知道公司的名字叫什么,他们在乎的只是这家公司的历史股价。相反,我们从不管这家公司过去的股价历史,反而希望尽量能够得到有助于我们了解这家公司的资讯,另外在我们买进股份之后,我们一点也不在意这家公司的股份在未来的几年是否有交易,就像是我们根本就不需要持有 100%股权的喜诗糖果或是布朗鞋业的股票报价来证明我们的权益是否存在,同样地,我们也不需要知道我们所持有的 7%可口可乐每天的股票行情。

我们认为,投资人应该真正评估的风险是,在预期的持有期内,他从一项投资所收到的税后收入总和(也包含出售股份所得),是否能够让他保有原来投资时拥有的购买力,并获得合理的回报率。虽然这样的风险无法做到像工程般的精确,但它至少可以做到足以做出有效判断的程度,影响评估的主要因素有下列几点:

1,这家公司长期竞争优势可以评估的确定性程度。

2,这家公司管理层可以衡量的确定性程度,包括管理层是否有能力充分发挥公司的潜能,以及是否有能力明智地运用现金的能力。

3,这家公司管理层以股东利益为导向可以评估的确定性程度,即管理层将企业获得的利益是实打实回报给股东还是中饱私囊(代理人成本)。

4,买进这家企业的价格。

5,税负和通货膨胀水平,这些将决定投资人的购买力回报缩水的程度。

这些因素对于许多分析师来说,可能是丈二和尚摸不着头脑,因为他们根本无法从任何类型的数据库中找到这些信息,但是取得这些精确数字的难度高,并不代表他们就不重要或是无法克服的。就像是司法正义一样,Stewart 大法官发现他根本无法找到何谓猥亵的标准,不过他还是坚称:只要我一看到就知道是不是。同样地对于投资人来说,不需靠精确的公式或是股价历史,也能以一种不太精确但却有用的方式,一眼就看到潜藏在某些投资里的风险。

就长期而言,可口可乐与吉列所面临的商业风险,远低于任何计算机公司或是零售商,可口可乐占全世界饮料销售量的 44%,吉列则拥有 60%的刮胡刀市场占有率(以销售额计),除了称霸口香糖的箭牌公司之外,我看不出还有那家公司可以像他们一样长期以来享有傲视全球的竞争力。

更重要的,可口可乐与吉列近年来也确实一点一滴地在增加他们全球市场的占有率,品牌的力量、产品的特质与分销渠道的优势,使得他们拥有超强的竞争力,就像是宽阔的护城河来保卫其经济城堡。相对的,一般公司却要在没有任何类似保护手段的情况下,每天耗尽心思去厮杀。就像是彼得·林奇所说的,对于那些只会销售相似产品的公司来说,大家应该在其股票上贴上警语:竞争有害于人类的财富。

可口可乐与吉列的竞争力在一般产业观察家眼中实在是显而易见的,然而其股票的 Beta 值却与一般平庸、完全没有竞争优势的公司相似,难道只因为这样我们就该认为在衡量公司所面临的产业风险时,完全不须考虑他们所享有的竞争优势吗?或者就可以说持有一家公司部分所有权,也就是股票的风险,与公司长期所面临的经营风险一点关系都没有?我们认为这些说法,包含衡量投资风险的 Beta 公式在内,一点道理都没有。

Beta 学者所架构的理论根本就没有能力去分辨,销售宠物玩具或呼拉圈的玩具公司,与销售大富翁或芭比娃娃的玩具公司,所隐藏的风险有何不同?但对一般普通的投资人来说,只要他略懂得消费者行为,以及形成企业长期竞争优势或弱势的原因的话,就可以很明确的看出两者的差别。当然每个投资人都会犯错,但只要将自己集中在相对少数,容易了解的投资个案上,一个理性、知性与耐性兼具的投资人一定能够将投资风险限定在可接受的范围之内。

当然有许多产业,连查理或是我可能都无法判断,到底我们面对的是宠物石头还是芭比娃娃,即使我们花了许多年时间去深入研究这些产业,还是无法解决这个问题。有时是因为我们本身知识上的缺陷,阻碍了我们对事情的理解,有时则是因为产业特性成为障碍。例如,对于一家随时都必须面临技术快速变迁的公司来说,我们根本就无法对其长期的竞争力做出任何的评断,人类在三十年前,是否就能预知现在电视制造或计算机产业的演进?当然不能,就算是大部分钻研于这方面领域的投资人与企业经理人也没有办法,那么为什么查理跟我要觉得应该要有去预测其它产业快速变迁前景的能力呢?我们宁愿挑些简单一点的,一个人坐的舒舒服服就好了,为什么还要费事去捡稻草里面的针呢?

当然,有些投资策略,例如我们从事多年的套利活动,就必须广泛多元化将风险分散,若是单一交易存在重大风险,就必须将投资分散到几个各自相互独立的标的之上,以降低总体风险。因此,只要确信你总体获得的收益(按概率加权)大大超过你的损失(同等加权) ,并能分散投资在一些类似但不相关的机会上,你就可以有意识地去投资一些风险资产,即那些确实有很大可能造成重大损失或伤害的投资。许多风险投资者用的就是这种方法,若是你也打算这样做的话,记得采取与赌场老板搞轮盘游戏同样的心态,他们鼓励大家持续不断的下注,因为长期而言,概率对他们有利,但他们会拒绝单笔巨大的赌注。

另外一种需要分散风险的特殊情况是,当投资人对特定行业不是特别的了解,不过他却对美国整体行业前景有信心,则这类的投资人应该分散持有许多公司的股份,同时将投入的时间拉长,例如,通过定期投资指数基金,一个什么都不懂的投资人通常都能打败大部分的专业经理人,很奇怪的是,当愚昧的金钱了解到自己的极限之后,它就不再愚昧了。

另一方面,若你是稍具常识的投资人,能够了解产业经济的话,应该就能够找出五到十家价格合理,并享有长期竞争优势的公司,此时一般分散风险的理论对你来说就一点意义也没有,要是那样做反而会伤害到你的投资成果并增加你的风险,我实在不了解那些投资人为什么要把钱投入他第 20 喜欢的业务上,而不是简单的把钱集中在他的最佳选择——最了解、风险最小,潜在盈利最大的业务之上,或许这就是女预言家 Mae West 所说的:好东西多多益善。

〔译文源于芒格书院整理的巴菲特致股东的信〕