巴菲特致股东的信(1984年)

⑥损失准备金中的盲点

损失准备金中的盲点

我认为所有在财产/意外险业务有重大投资的股东,都应该对财务报告中利润的固有盲点有所了解。PhilGraham 在担任华盛顿邮报的发行人时曾说:“新闻日报是攥写历史的第一手草稿”。不幸的是,财产险所提供的财务报告,充其量只是该公司收益和财务状况的初稿。

主要的问题在于成本的确定,保险公司的大部分成本来自索赔损失,而对于当年的保费收入未来会发生多少索赔损失实在是难以估计,有时损失的发生以及其损害程度要在好几十年之后才会明朗。

一般来说,产险业当年度认列的损失主要包含有下列几项:(1)赔付支出:当年已发生且支付的损失,(2)未决赔款准备金 A:对于已发生且已提报,但仍未结清的损失,(3)未决赔款准备金 B:对于已发生但尚未提报,亦即保险业者尚不知情案件所作的估计损失 (IBNR:发生了但尚未提报),(4)今年对于过去几年前述(2)(3)项估计损失所作的修正影响。

此类修正可能会推迟很久,但最终导致先前在 X 年收入误报的任何损失都必须更正,不论是在 X+1 或是X+10 年,而这无可避免地导致修正年度的损益数字也被扭曲。例如,假设一位索赔人在 1979 年被我们一位投保户所伤,而承保时估计的理赔金额为一万美元,所以我们在当年损益表提列了一万美元的损失准备。而在 1984年双方以十万美元合解,我们必须在 1984 年另行认列九万美元的赔付损失,尽管该项损失属于 1979 年的成本。如果假设这笔业务是在 1979 年的唯一经营活动,则我们会在成本上严重误导自己,而在收益上误导你们。

在汇总财产险损益表中极具欺骗性但看似精确的数字时,必须广泛使用估计值,这意味着无论管理层的意图多么正确,都必然渗入许多错误的估计值。而为了减少这类错误,大多数的保险公司运用各种统计方法来调整成千上万的被保险人的损失评估(被称为案例准备金),这些评估作为估计损失准备金总额的基础数据。调整产生的额外储备被标记为“损失准备金、未决赔付的、补充性的”不同类目,调整的目标应该是当财务报表日期之前发生的所有损失最终得到支付时,损失准备金高估部分 VS 低估部分最终接近相抵。

在伯克希尔,我们已经增加了我们认为适当的损失补充储备金,但近年来这些储备并不充足。重要的是,你必须了解我们的过去所涉及的损失准备提列错误的严重程度。因此,你可以亲眼看到整个过程有多不精确,也可以判断我们是否可能存在一些系统性偏见,以让你对我们当前和未来的数据保持警惕。

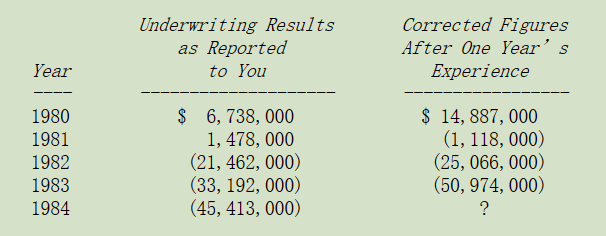

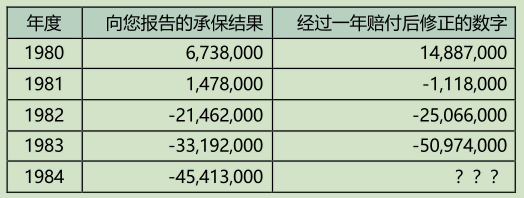

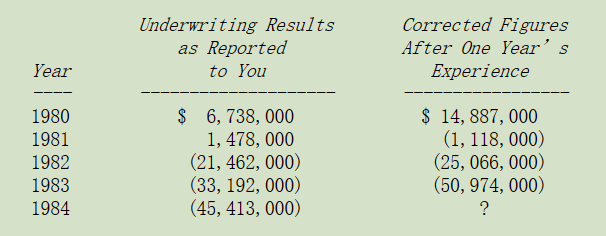

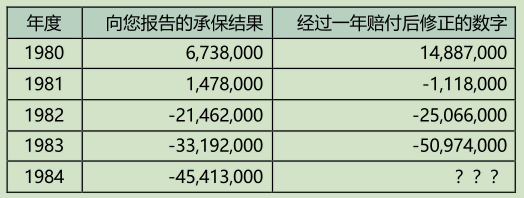

下表第一列显示过去五年我们跟各位报告的保险承销业绩,同时并提供一年之后以”如果当时我们知道那么我们认为我们现在知道什么”的基础下的估算数字,而所谓地”我们认为我们现在知道什么”系因为这其中还包含许多对以前发生的损失所作的估计调整,然而,由于前几年的许多索赔过去一年已经得到解决,因此我们对一年后的估计值中所包含的猜测工作要比之前的要少:

本表不包括我们的结构性结算和损失准备假设业务。有关损失准备金经验的重要额外资料载于第43至45页。

为了帮助各位进一步理解上表,让我们用最新的数据加以解释:1984 年报告的税前承保损失为 4,540 万,其中 2,760 万为 1984 年度我们估计将会发生的损失,加上 1983 年度 1,780 万新增加的损失修正数字。

正如上表你所看到的,我跟各位报告的数字与实际所发生的数字有很大的出入,而且这几年的报告的数字比实际的要好,这让我觉得非常地懊恼,因为(1)我一向希望你能相信我说过的话,(2)毫无疑问我和保险经理人若早点发现估计不足造成承保损失的严重性一定会及时采取行动,(3)我们低估损失夸大了收入,相当于多缴了本来不应该付的税金。虽然这些税金早晚会修正回来,只是时间拉得越长,我们损失的利息就越多。

由于我们业务的侧重于意外险与再保险业务,比起专注财产保险的公司,我们在估计损失成本上存在更多问题。当你承保的一栋建筑物烧毁了,你可以很快地在损失成本上作反应,而如果向你投保的雇主发现他一名退休的员工,在几十年前因工作关系感染某种疾病,你反应则繁琐很多。即便如此,但我仍然觉得我们的错误令人尴尬。在直接承保部分,我们大大低估了法院及陪审团不顾事实真相与过去判例对损害赔偿的认定,而要求我们这些所谓深口袋付钱的群起效应(deep pocket 即口袋深有大钱的金主儿),我们也低估了一般大众对于受伤者应获得巨额补偿对陪审团的传染效应。在再保险部分,我们提列准备金不足方面有最糟糕的经验,向我们寻求再保的保险公司也犯了相同的错误,由于我们提列储备是依据对方提供的资料,他们的错误就变成了我们的错误。

最近我听到的一则故事可以用来说明我们保险会计问题,一个人海外旅行期间接到姐姐电话,父亲因意外去世了,由于一时无法赶回国内参加丧礼,他便交待姐姐处理一切丧葬事宜并允诺负责所有费用。当他回国后不久,收到一张几千美金的帐单,他立即就付了钱。接下来一个月又收到一张 15 美元的帐单,他也付了钱。又过一个月又收到类似的帐单,当第三张 15 美元账单出现时,他终于忍不住打电话问出了什么事,电话那头表示:“噢! 我忘了告诉你。我用租来的衣服埋葬了爸爸。”

如果近几年你是从事保险业务,尤其是再保险业务的话,这段故事可能会让你很心痛。尽管我们已尽可能在当期的财务报表上包含所有类似「西装租金式」的负债,但过去几年的报表却令我们感到汗颜,也足以让各位的起疑,以后年报中我将持续跟你们报告每年出现的错误,不论是有利或是不利的。

当然不是所有愚蠢的准备金不当的错误都是无心之过,随着承保绩效持续恶化,管理层在损失准备提列乃至于财务报表表达上有很大的自由裁量权,所以人性黑暗的一面便彰显出来,有些公司若真正认真去评估其可能发生的损失成本的话,那些即将倒闭的公司不得不对这些尚未支付的潜在赔偿持非常乐观的看法。其他有些则从事一些可以将损失暂时隐藏起来的交易行为。

这两种方法都可以在相当长的时间内发挥作用:外部独立的审计师也很难有效地对这类行为加以规范制止,当一家保险公司的负债实际上大于资产时,通常公司自己应该宣告破产,在这种羞于破产的制度下,尸体本身通常会一再给自己翻案复活的机会。

当然,在大多数企业中,资不抵债的公司会耗尽现金。但保险公司的情况却非如此,虽已破产但还手握重金。因为保费是从保户一开始投保时便收到,但理赔款却是在损失发生之后许久才须支付,所以一家保险公司可能要在耗尽净值之后许久才会真正耗完现金。而事实上这些所谓行尸走肉,通常会铤而走险,卯尽全力不计成本来吸收保单,只为现金持续流入,这些公司的态度就好象一个挪用公款的人把偷来的资金输掉了一样,期望下一次能够幸运的捞回本钱以弥补以前的亏空。即使他们不走运亏损持续扩大,反正亏一亿跟亏一千万对管理层的惩罚差别不大,但管理层却能继续保有原来的职位与待遇。

伯克希尔对其他财产/意外险公司的损失准备金错误的关注超过了学术界的兴趣。我们不但身受那些活死人不惜一切代价的竞争之痛,当他们真的倒闭时,我们也要跟着倒霉,因为许多州政府设立的偿债基金系依照保险业经营状况来征收,伯克希尔最后被迫要来分担这些损失的一部分,且由于这些错误通常要很晚才会发现,事件会远比想象中严重,甚至产生连锁效应,那些原本体质较弱但不致倒闭的小公司可能因几家大型保险公司的破产而殃及倒闭,最后如滚雪球一般,一发不可收拾。如果监管当局能对那些烂公司迅速识别并强制破产,则可以减轻此类危险,但目前这方面进展缓慢。

〔译文源于芒格书院整理的巴菲特致股东的信〕